These past few months I was a teaching assistant for a class on parallel computer architecture. One of the questions on our first homework assignment asked the students to analyze a function and realize that it could not be optimized any further because it was already at maximum memory bandwidth. But a student pointed out, rightly, that it was only at half the maximum bandwidth. In an attempt to understand what was going on, I embarked on a quest to write a program that achieved the theoretical maximum memory bandwidth.

tl;dr

Use non-temporal vector instructions or optimized string instructions to get the full bandwidth.

What is memory bandwidth?

When analyzing computer programs for performance, it is important to be aware of the hardware they will be running on. There are two important numbers to pay attention to with memory systems (i.e. RAM): memory latency, or the amount of time to satisfy an individual memory request, and memory bandwidth, or the amount of data that can be accessed in a given amount of time1.

It is easy to compute the theoretically maximum memory bandwidth. My laptop has 2 sticks of DDR3 SDRAM running at 1600 MHz, each connected to a 64 bit bus, for a maximum theoretical bandwidth of 25.6 GB/s2. This means that no matter how cleverly I write my program, the maximum amount of memory I can touch in 1 second is 25.6 GB. Unfortunately, this theoretical limit is somewhat challenging to reach with real code.

Measuring memory bandwidth

To measure the memory bandwidth for a function, I wrote a simple benchmark. For each function, I access a large3 array of memory and compute the bandwidth by dividing by the run time4. For example, if a function takes 120 milliseconds to access 1 GB of memory, I calculate the bandwidth to be 8.33 GB/s. To try to reduce the variance and timing overhead, I repeatedly accessed our array and took the smallest time over several iterations5. If you're curious, all my test code is available on github.

A first attempt

I first wrote a simple C program to just write to every value in the array.

void write_memory_loop(void* array, size_t size) {

size_t* carray = (size_t*) array;

size_t i;

for (i = 0; i < size / sizeof(size_t); i++) {

carray[i] = 1;

}

}

This generated the assembly I was expecting:

0000000100000ac0 <_write_memory_loop>:

100000ac0: 48 c1 ee 03 shr $0x3,%rsi

100000ac4: 48 8d 04 f7 lea (%rdi,%rsi,8),%rax

100000ac8: 48 85 f6 test %rsi,%rsi

100000acb: 74 13 je 100000ae0 <_write_memory_loop+0x20>

100000acd: 0f 1f 00 nopl (%rax)

100000ad0: 48 c7 07 01 00 00 00 movq $0x1,(%rdi)

100000ad7: 48 83 c7 08 add $0x8,%rdi

100000adb: 48 39 c7 cmp %rax,%rdi

100000ade: 75 f0 jne 100000ad0 <_write_memory_loop+0x10>

100000ae0: f3 c3 repz retq

But not the bandwidth I was expecting (remember, my goal is 23.8 GiB/s):

$ ./memory_profiler

write_memory_loop: 9.23 GiB/s

Using SIMD

The first thing I tried is to use Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD) instructions to touch more memory at once. Basically, a modern processor is very complicated and has multiple Arithmetic Logic Units (ALUs). This gives it the ability to support instructions that perform an operation on multiple pieces of data simultaneously. I will use this to perform operation on more data simultaneously to get higher bandwidth. Since my processor support AVX instructions, I can perform operations on 256 bits (32 bytes) every instruction:

#include <immintrin.h>

void write_memory_avx(void* array, size_t size) {

__m256i* varray = (__m256i*) array;

__m256i vals = _mm256_set1_epi32(1);

size_t i;

for (i = 0; i < size / sizeof(__m256i); i++) {

_mm256_store_si256(&varray[i], vals); // This will generate the vmovaps instruction.

}

}

But when I use use this, I didn't get any better bandwidth than before!

$ ./memory_profiler

write_memory_avx: 9.01 GiB/s

Why was I consistently getting slightly under half the theoretical memory bandwidth?

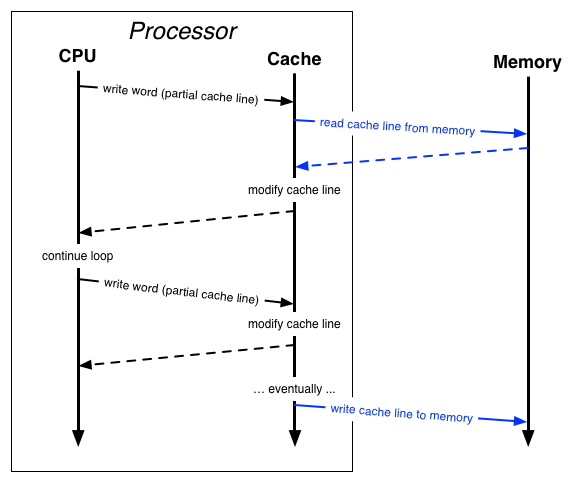

The answer is a bit complicated because the cache in a modern processor is complicated6. The main problem is that memory traffic on the bus is done in units of cache lines, which tend to be larger than 32 bytes. In order to write only 32 bytes, the cache must first read the entire cache line from memory and then modify it. Unfortunately, this means that my program, which only writes values, will actually cause double the memory traffic I expect because it will cause reads of cache line! As you can see from the picture below, the bus traffic (the blue lines out of the processor) per cache line is a read and a write to memory:

Non-temporal instructions

So how do I solve this problem? The answer lies in a little known feature: non-temporal instructions. As described in Ulrich Drepper's 100 page What every programmer should know about memory,

These non-temporal write operations do not read a cache line and then modify it; instead, the new content is directly written to memory. This might sound expensive but it does not have to be. The processor will try to use write-combining (see section 3.3.3) to fill entire cache lines. If this succeeds no memory read operation is needed at all.

Aha! I can use these to avoid the reads and get our full bandwidth!

void write_memory_nontemporal_avx(void* array, size_t size) {

__m256i* varray = (__m256i*) array;

__m256i vals = _mm256_set1_epi32(1);

size_t i;

for (i = 0; i < size / sizeof(__m256); i++) {

_mm256_stream_si256(&varray[i], vals); // This generates the vmovntps instruction.

}

}

I run our new program and am disappointed again:

$ ./memory_profiler

write_memory_nontemporal_avx: 12.65 GiB/s

At this point I'm getting really frustrated. Am I on the right track? I quickly compare our benchmarks to memset:

$ ./memory_profiler

write_memory_memset: 12.84 GiB/s

and see that while I am far from the theoretical bandwidth, I'm at least on the same scale as memset. So now the question is: is it even possible to get the full bandwidth?

Repeated string instructions

At this point, I got some advice: Dillon Sharlet had a key suggestion here to use the repeated string instructions. The rep instruction prefix repeats a special string instruction. For example, rep stosq will repeatedly store a word into an array - exactly what I want. For relatively recent processors7, this works well. After looking up the hideous syntax for inline assembly8, I get our function:

void write_memory_rep_stosq(void* buffer, size_t size) {

asm("cld\n"

"rep stosq"

: : "D" (buffer), "c" (size / 8), "a" (0) );

}

And when I run, I get results that are really close to the peak bandwidth:

$ ./memory_profiler

write_memory_rep_stosq: 20.60 GiB/s

Now the plot thickens. It turns out that it is indeed possible to get the full memory bandwidth, but I can't get close with my non-temporal AVX instructions. So what is up?

Multiple cores

Again, Dillon Sharlet provided an important insight: the goal of saturating the entire bandwidth with a single core was perhaps a bit extreme. In order to use the full bandwidth, I would need to use multiple cores. I used OpenMP to run the function over multiple cores. To avoid counting the OpenMP overhead, I computed the timings only after all threads are ready and after all threads are done. To do this, I put barriers before the timing code:

#pragma omp parallel // Set OMP_NUM_THREADS to the number of physical cores.

{

#pragma omp barrier // Wait for all threads to be ready before starting the timer.

#pragma omp master // Start the timer on only one thread.

start_time = monotonic_seconds();

// The code we want to time.

#pragma omp barrier // Wait for all threads to finish before ending the timer.

#pragma omp master // End the timer.

end_time = monotonic_seconds();

}

When I run, I get very reasonable output (remember, the goal is 23.8 GiB/s):

$ OMP_NUM_THREADS=4 ./memory_profiler # I only have 4 physical cores.

write_memory_avx_omp: 9.68 GiB/s

write_memory_nontemporal_avx_omp: 22.15 GiB/s

write_memory_memset_omp: 22.15 GiB/s

write_memory_rep_stosq_omp: 21.24 GiB/s

Final thoughts

Finally! We are within 10% of our theoretically maximum bandwidth. I'm tempted to try to squeeze out some more bandwidth, but I suspect there isn't much more that I can do. I think any more performance would probably require booting the machine into a special configuration (hyper threading and frequency scaling disabled, etc) which would not be representative of real programs.

I still have some unanswered questions (I will happily buy a beer for anyone who can give a compelling answer):

- Why doesn't

write_memory_avx_omp, the function that uses AVX to store (but doesn't use non-temporal instructions) use half the bandwidth? - Why doesn't the use of non-temporal instructions double bandwidth for the single core programs? It only went up 50%.

- Why aren't the AVX instructions on one core able to saturate the bandwidth ?

- Why don't AVX instructions get roughly double the bandwidth of the SSE instructions?

- Why doesn't

rep scansqorrep lodsqget the same bandwidth asrep stosq?

-

This lecture from the course is very good at illustrating some of these concepts. ↩

-

I'm not completely convinced this math is correct, but this number lines up with the specs provided by Intel for my processor as well. ↩

-

It should be too large to fit in cache since I want to test memory throughput, not cache throughput. ↩

-

Use a monotonic timer to avoid errors caused by the system clock. ↩

-

For future work, I'll probably write a kernel module in the style of this excellent Intel white paper. ↩

-

Ok, the answer is actually fairly complicated and I'm going to lie just a little bit to simplify things. If you're curious how a modern cache works, you should read through the lectures on it. ↩

-

Apparently, this wasn't always the case: http://stackoverflow.com/a/8429084/447288. In addition, my benchmarking seems to indicate that neither

rep lodsqorrep scansqbenefit from the same degree of optimization thatrep stosqreceived. I don't fully understand what all is going on. ↩ -

The inline assembly wasn't strictly necessary here (I could have and should have written it directly in an assembly file), but I've had difficulties exporting function names in assembly portably. ↩

Comments !